Constructivism

What is meant by constructivism? The term refers to the idea that learners construct knowledge for themselves---each learner individually (and socially) constructs meaning---as he or she learns. Constructing meaning is learning; there is no other kind. Therefore we have to focus on the learner in thinking about learning (not on the subject/lesson to be taught and there is no knowledge independent of the meaning attributed to experience (constructed) by the learner, or community of learners.

There are two main subsets of research that the constructivist approach to teaching and learning is based on; they are cognitive psychology and social psychology. Piaget (1972) is considered as one of the chief theorists among the cognitive constructivists, while Vygotsky (1978) is the major theorist among the social constructivists.

Swiss epistemologist Jean Piaget (1896-1980) devoted much of his life to the study of child development in the learning process. One of the basic premises, upon which much of his work in the theory of constructivism was built, is that for learning to take place, the child's view of the world must come into conflict with his actual experience of that world. It is when the child puts forth effort to reconcile the two, his expectations and his experiences, that he is able to learn.

Lev Vygotsky, born in the U.S.S.R. in 1896, is responsible for the social development theory of learning. He proposed that social interaction profoundly influences cognitive development. Central to Vygotsky's theory is his belief that biological and cultural development do not occur in isolation (Driscoll, 1994).

Vygotsky approached development differently from Piaget. Piaget believed that cognitive development consists of four main periods of cognitive growth: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operations, and formal operations (Saettler, 331). Piaget's theory suggests that development has an endpoint in goal. Vygotsky, in contrast, believed that development is a process that should be analysed, instead of a product to be obtained. According to Vygotsky, the development process that begins at birth and continues until death is too complex to be defined by stages (Driscoll, 1994; Hausfather, 1996).

The importance of prior knowledge. Advocates of a constructivist approach suggest that educators first consider the knowledge and experiences students bring with them to the learning task. The school curriculum should then be built so that students can expand and develop this knowledge and experience by connecting them to new learning.

Piaget’s particular insight was the role of maturation (simply growing up) in children's increasing capacity to understand their world: they cannot undertake certain tasks until they are psychologically mature enough to do so. This process is not wholly gradual, however. Once a new level of organization, knowledge and insight proves to be effective, it will quickly be generalized to other areas. As a result, transitions between stages tend to be rapid and radical, and the bulk of the time spent in a new stage consists of refining this new cognitive level. When the knowledge that has been gained at one stage of study and experience leads rapidly and radically to a new higher stage of insight, a "gestalt" is said to have occurred.

It is because this process takes this dialectical form, in which each new stage is created through the further differentiation, integration, and synthesis of new structures out of the old, that the sequence of cognitive stages are logically necessary rather than simply empirically correct. Each new stage emerges only because the child can take for granted the achievements of its predecessors, and yet there are still more sophisticated forms of knowledge and action that are capable of being developed.

The four development stages are described in Piaget's theory as

1. Sensorimotor stage: from birth to age 2 years (children experience the world through movement and senses and learn object permanence)

2. Preoperational stage: from ages 2 to 7 (acquisition of motor skills)

3. Concrete operational stage: from ages 7 to 11 (children begin to think logically about concrete events)

4. Formal Operational stage: after age 11 (development of abstract reasoning).

Vygotsky believed that this life long process of development was dependent on social interaction and that social learning actually leads to cognitive development. This phenomenon is called the Zone of Proximal Development. Vygotsky describes it as "the distance between the actual development level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers" (Vygotsky, 1978). In other words, a student can perform a task under adult guidance or with peer collaboration that could not be achieved alone. The Zone of Proximal Development bridges that gap between what is known and what can be known. Vygotsky claimed that learning occurred in this zone.

“Because Vygotsky asserts that cognitive change occurs within the zone of proximal development, instruction would be designed to reach a developmental level that is just above the student's current developmental level. Individuals participating in peer collaboration or guided teacher instruction must share the same focus in order to access the zone of proximal development. "Joint attention and shared problem solving is needed to create a process of cognitive, social, and emotional interchange" (Hausfather, 1996).

Reflection plays an important role in both theories.

Vygotsky

Scaffolding and reciprocal teaching are effective strategies to access the zone of proximal development. Scaffolding requires the teacher to provide students the opportunity to extend their current skills and knowledge. The teacher must engage students' interest, simplify tasks so they are manageable, and motivate students to pursue the instructional goal. In addition, the teacher must look for discrepancies between students' efforts and the solution, control for frustration and risk, and model an idealized version of the act (Hausfather, 1996). Reciprocal teaching allows for the creation of a dialogue between students and teachers. This two way communication becomes an instructional strategy by encouraging students to go beyond answering questions and engage in the discourse (Driscoll, 1994; Hausfather, 1996). Cognitively Guided Instruction is another strategy to implement Vygotsky's theory. This strategy involves the teacher and students exploring problems and then sharing their different problem solving strategies in an open dialogue (Hausfather, 1996).

Piaget

By showing how children progressively enrich their understanding of things by acting on and reflecting on the effects of their own previous knowledge, they are able to organize their knowledge in increasingly complex structures. At the same time, by reflecting on their own actions, the child develops an increasingly sophisticated awareness of the ‘rules’ that govern in various ways. For example, it is by this route that Piaget explains this child’s growing awareness of notions such as ‘right’, ‘valid’, ‘necessary’, ‘proper’, and so on. In other words, it is through the process of objectification, reflection and abstraction that the child constructs the principles on which action is not only effective or correct but also justified.

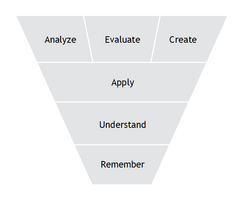

Both theories promote deeper higher learning.

Piaget

"...The incredible failing of traditional schools till very recently has been to have almost systematically neglected to train pupils in experimentation. It is not the experiments the teacher may demonstrate before them, or those they carry out themselves according to a pre-established procedure, that will teach students the general rules of scientific experimentation--such as the variation of one factor when the others have been neutralized (ceteris paribus), or the dissociation of fortuitous fluctuations and regular variations. In this context more than in any other, the methods of the future will have to give more and more scope to the activity and the groupings of students as well as to the spontaneous handling of devices intended to confirm or refute the hypothesis they have formed to explain a given elementary phenomenon. In other words, if there is any area in which active methods will probably become imperative in the full sense of the term, it is that in which experimental procedures are learned, for an experiment not carried out by the individual himself with all freedom of initiative is by definition not an experiment but mere drill with no educational value: the details of the successive steps are not adequately understood."

--Piaget, To Understand is to Invent

Vygotsky

"The psychological prerequisites for instruction in different school subjects are to a large extent the same; instruction in a given subject influences the development of the higher functions from beyond the confines of that particular subject; the main psychic functions involved in studying various subjects are interdependent--their common bases are consciousness and deliberate mastery, the principal contributions of the school years. It follows from these findings that all the basic school subjects act as formal discipline, each facilitating the learning of the others; the psychological functions stimulated by them develop in one complex process."

--Vygotsky, Thought and Language, p. 186